One of the most common things I hear from parents is that their child doesn’t respond to rewards or punishments. It’s a source of tremendous frustration for parents, often leaving them without much hope for things to get better. It’s easy to see how hopeless parents can feel after saying things like “I’ve tried taking the cell phone away and that just made things worse.” Or after “I tried telling him he can’t go out with friends but that didn’t work. Nothing works!”

One of the most common things I hear from parents is that their child doesn’t respond to rewards or punishments. It’s a source of tremendous frustration for parents, often leaving them without much hope for things to get better. It’s easy to see how hopeless parents can feel after saying things like “I’ve tried taking the cell phone away and that just made things worse.” Or after “I tried telling him he can’t go out with friends but that didn’t work. Nothing works!”

There are a few reasons why a system of rewards and punishments may not work. First and foremost, if you are a parent, you must define a specific behavior for a child. If he/she gets points for “being good” and loses them for “being bad,” he/she won’t change because he doesn’t know what he needs to do to earn or lose points. When he/she earns points he/she may be happy but when he/she loses points, everything seems unfair because he/she didn’t realize he/shr was doing to lose points for his/her behavior.

You also need a reward that the child genuinely desires and a consequence they genuinely don’t want. You might think they are willing to work for chocolate, but maybe they aren’t. You might think that they hate it when you yell at them, but maybe they don’t.

But let’s assume that you have a well defined behavior plan with appropriate rewards and punishments (Click here to help create one) Another reason why behavior plans fail is that behavior typically becomes worse, not better, in the early phases. The increase in a behavior after you eliminate its reinforcers is called a response burst. Put less technically, it refers to your child doing something problematic more often (rather than less often) after they stop getting the desired results. his is actually natural. Let’s look at a two examples to help make this clear.

Example 1:

“My child complains or whines when he doesn’t get his way.” This often happens at the grocery store where we fight about unhealthy food choices. Because it is frustrating to listen to my child whine incessantly, and I feel embarrassed when my child has a tantrum in public, I often give-in and buy him the ice-cream he so badly wants.

Now, I take my child to a trained cognitive behavioral therapist. The therapist explains to me that despite my best intentions, I’m actually increasing the likelihood that my child is going to whine again in the future.

The logic goes like this: behaviors that are followed by desirable outcomes are likely to be repeated. In this case, the behavior is whining and the outcome is getting ice-cream. Since getting ice-cream is a desired outcome that comes after whining, he is going to whine again in the future. Next the therapist tells me, we are going to explain to your child what it means to complain or whine. We’ll also make it so that each time your child complains or whines he loses 50 cents from his weekly allowance of $10. I think, “this sounds like a good idea. He does like getting that allowance.” So the therapist, my son and me all sit down together and explain this new system and I leave the therapist’s office feeling hopeful.

We go straight to the grocery store and sure enough my son starts asking for ice-cream. I say with a newfound hope, “No ice-cream today. And remember, if you whine about it you lose 50 cents for each time you whine.” Sadly, instead of adaptively responding to the new rules, my child protests “that’s not fair!” Instead of stopping quickly, he has the largest melt-down ever, way bigger than before I ever went to see the psychologist! I start thinking, “boy that didn’t help at all. What a waste of time and money!”

Now let’s ask, what went wrong in this scenario? You may be surprised to learn that nothing went wrong! The only change to be made is that my therapist should have prepared me for this ordeal. My child displayed a natural response burst. The frequency and intensity of his whining increased because he no longer got the desired outcome.

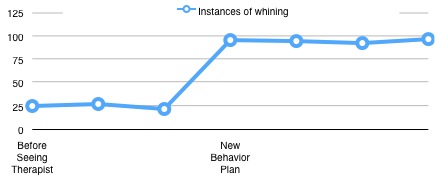

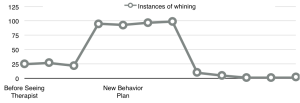

Let’s look at this situation in a graph form. Across the horizontal line (x-axis), you have Time. Across the vertical line (y-axis) you have total instances of whining. Before the behavior plan, my son was whining/complaining around 25 times each time we went to the grocery store. When we start implementing the plan, his complaints sky rocket to almost 100 times in one visit!

Parents are often a bit confused by the child’s behavior. They think, “if he knows he’s not going to get the reward, why does he bother to keep whining?” The answer to this is complex, but lets turn the tables and see if we can better understand the behavior.

Example 2:

I’m working hard on a project that is due to my boss in an hour. I double-click “save” expecting my project to save, but nothing happens. Then I double click again—again nothing. Then again—nothing happens. Then I start clicking rapidly. I wait a minute trying to calm myself down and then I try again, and again… I know my computer is frozen but for some reason I keep clicking hoping that it won’t be or that it was only temporary. This is an example of a very common response burst. My behavior (clicking save) is increasing in frequency because I’m not getting the desired outcome. When suddenly the desired outcome doesn’t occur, do I completely switch gears and say “I guess clicking isn’t working anymore, I should try another strategy?” Certainly I don’t. Rather I do some things that may seem a bit strange to an outsider. Sometimes I click harder or faster. You may see me tapping it so strongly that it may look like I’m trying to shake something loose from inside it.

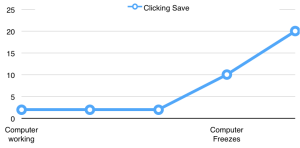

Again, let’s take a look at this in a graph format. The horizontal axis represents time and the vertical axis is number of times I click “save.” Before my computer freezes, I double click save every couple of minutes. But when it freezes, I double click rapidly up to 20 times!

Looking at these graphs: one could reasonably conclude that freezing the computer doesn’t stop me from clicking and actually makes it worse. Likewise, punishing my son rather than giving him ice-cream seems to have made him way worse!

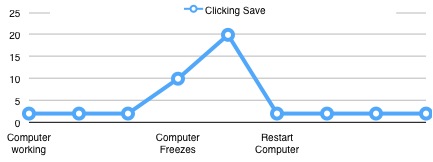

But those graphs are only half the picture. Do I keep clicking and clicking forever? Certainly not. My temporary state of seemingly irrational clicks usually doesn’t last very long. Eventually, I give in and restart the computer (change my strategy). Then my clicking behavior returns to it’s normal frequency. So the full graph looks like this.

The same exact thing will happen with my son. If I can tolerate his massive tantrum and not give him the ice-cream, he may repeat the tantrum again the next time we’re at the store. And if we’re particularly unlucky, he may try a few more times. But it won’t take long for him to give up and change strategies. So the full graph looks like this.

The giant “humps” you see in the middle of these last two graphs are the response bursts. The behaviors temporarily increase in frequency (and sometimes intensity) when the desired outcome doesn’t occur.

Notice that if I don’t get all the way through the response burst, it does in fact look like all I’ve done is made things way worse. If you don’t hold out until the response burst ends, then you will have made matters worse. Your child will have accidentally learned a very sinister lesson “it’s not enough to whine 25 times. I have to whine 100 times to get what I want!”

Because response bursts are difficult to tolerate, it’s important you not begin working on a behavior plan unless you are ready to make space for a brief worsening of behavior. So ask yourselves, “Are we willing to listen to experience a brief but possibly intense worsening of our child’s behavior in the service of eliminating our child’s name-calling/yelling/verbal-abuse/non-compliance or aggressive behavior?” If the answer is yes, then it’s time to get started. If the answer is no, then it’s time to start thinking about how you can get ready or whether you truly want to change the behavior. One way to start getting ready is to see a therapist who can help you learn to tolerate and accept these tantrums in the service of a better life for your family.

———————————————————————————————————————————————

References:

Ramnero, J. & Trbejem B, (2011) The ABCs of Human Behavior. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications.